The typical Anatomy of Sharks

Sharks are not stupid eating machines. Their brain and body are specialized and highly developed for hunting. Their cartilage skeleton is light and elastic. Their oily liver serves as a buoyancy device and energy storage. The spirally folded intestine or spiral valve is a special feature of cartilaginous fish. Special vascular nets (miracle nets) enable some species to keep their body temperature above the ambient temperature, such as of birds and mammals.

Photo © Shark Foundation

Photo © Shark Foundation

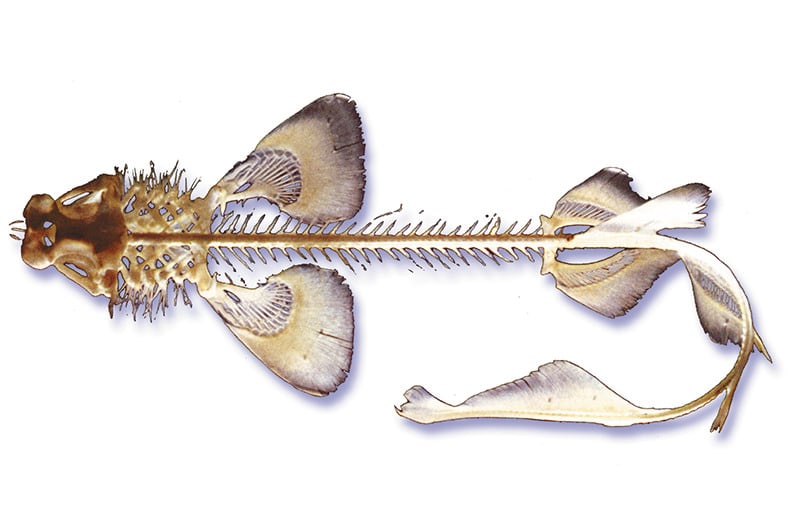

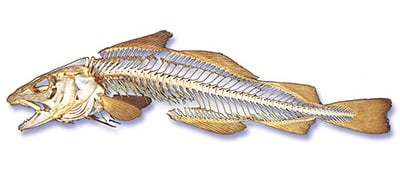

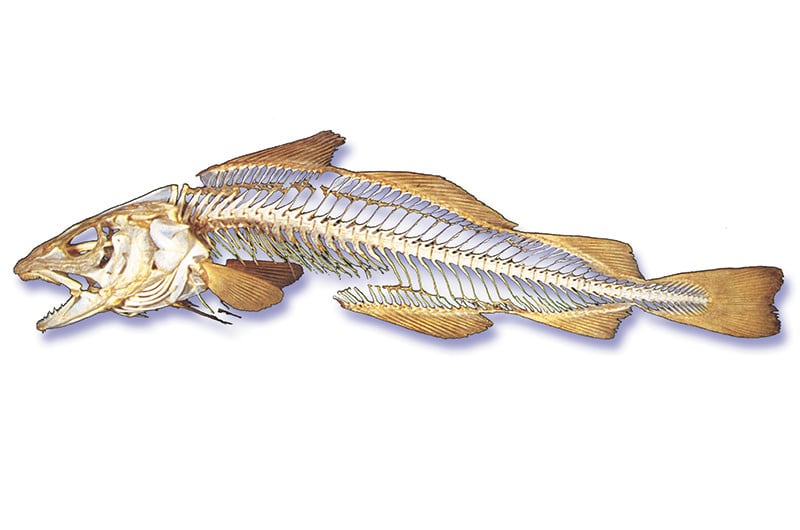

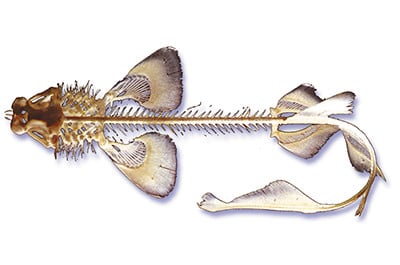

Cartilaginous Skeleton

Sharks have a spine, so they belong to the vertebrates. Their spine and their whole skeleton, however, are not made of bones, as with bony fish such as cod, tuna or salmon, but of cartilage. For this reason, sharks, together with rays and chimeras, belong to the class of cartilaginous fish. The class of cartilaginous fish has separated from the class of bony fish over 400 million years ago.

A cartilaginous skeleton has advantages, especially for aquatic species. It is lighter and more elastic than a skeleton of calcareous bones. Nevertheless, it offers the necessary robustness to support even very large sharks such as whale sharks or basking sharks, which grow to over 10 m in length. And it can, in regions that are heavily stressed such as the jaws, be reinforced with bone substance.

Unfortunately, this practical skeleton also has its disadvantages. The fins of sharks with their many cartilaginous fin rays are the death sentence for millions of sharks every year. For an unknown reason shark fin soup has become a prestigious food in Asia. It cannot be the taste of the cartilage, which has almost no taste whatsoever.

Photo © Shark Foundation

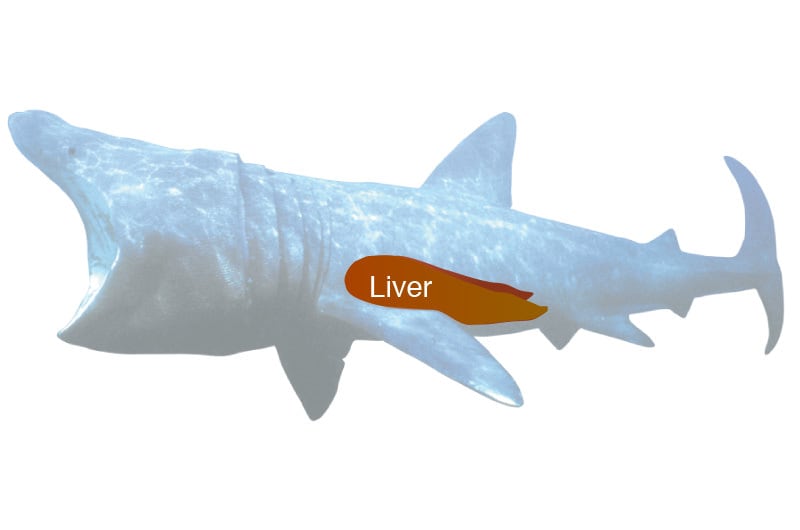

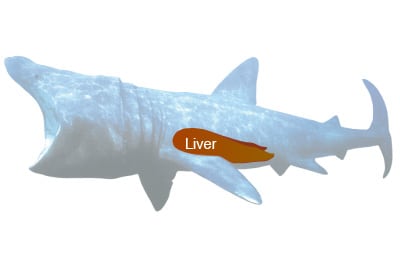

The Liver

The liver of sharks can become very large (up to 30% of their body weight) and contains up to 90% different fats and oils which are lighter than water. Sharks thus also use their liver as a buoyancy device which makes them very elegant swimmers. Most bony fish have an air bladder which provides buoyancy and sometimes trouble. Air expands much more than oil at higher temperatures. When a bony fish moves to a warmer water region, it either drifts upwards or has to get rid of the excess air by burping.

The liver serves primarily as a food reserve and can shrink to half its volume during a longer fast. But it also seals the fate of many shark species who are hunted because of their liver. Shark liver oils are used as a food additive, a base for lubricants and cleaning agents, in leather tanning or in the cosmetic and pharmaceutical industry. Cod liver oil, notorious among many children, comes either from cod or shark or a mixture of the two.

Up to 1000 kg of oil can be extracted from the liver of basking sharks. The hunt for shark oil has been a disaster for these sharks who have been fished almost to extinction. Today they are a highly endangered species under strict protection.

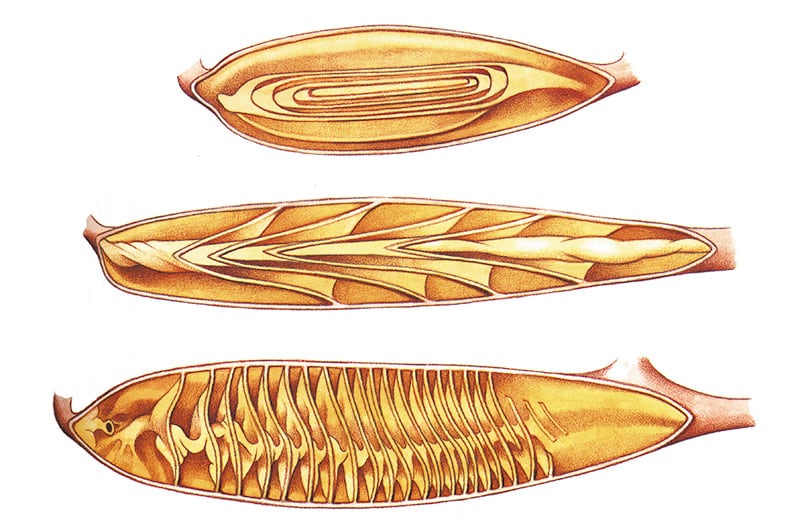

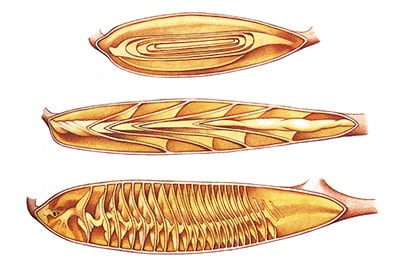

The Spiral Valve

The spiral valve is typical for sharks. Its specially spirally folded inner wall increases the absorption surface for nutrients without lengthening the intestine. This allows the food to be optimally absorbed and used. The number of folds varies between a few and several dozen. The wrinkles can have the shape of a scroll lying lengthwise to the intestine or a simple ring shape.

Photo © Dietmar Weber

Warmer is faster and better

Body temperature

Biological processes are heat-dependent, the warmer the faster they function. At a certain temperature, e.g. 36 to 37° Celsius in humans, an organism functions optimally. Mammals and birds can maintain their body temperature at a constant level regardless of the ambient temperature they remain equally warm. Reptiles, amphibians, bony fish and sharks usually have varying temperatures. This means that their body temperature, like the ambient temperature, can fluctuate greatly.

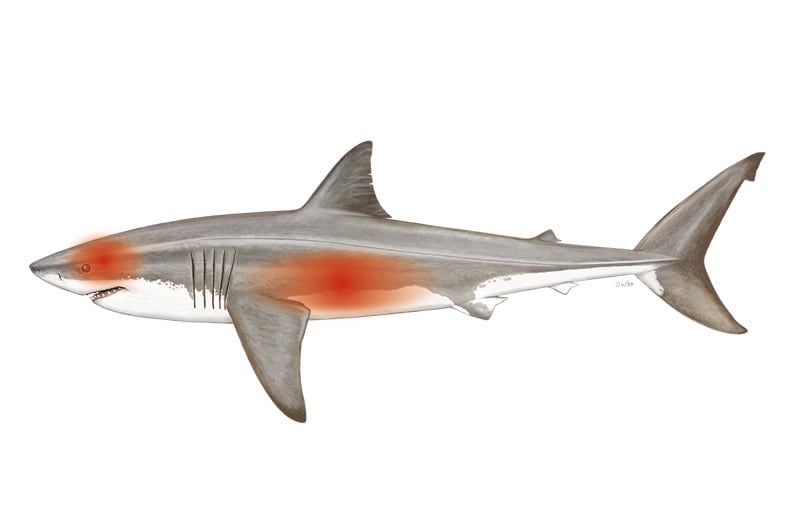

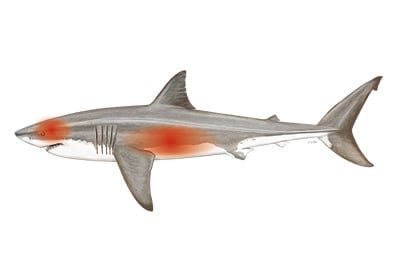

Heating with a heat exchanger

In sharks, the blood warms up as it flows through the body because muscle movement and various chemical reactions generate heat. When flowing through the gills, however, the warmer blood coming out of the body is cooled down to ambient temperature. For example, sharks that hunt seals are at a disadvantage because seals have a constant high body temperature. However, some sharks of the Lamnid family – such as white sharks, thresher sharks, makos or porbeagles – have developed a heat exchanger heating system that enables them to keep parts of their body above the ambient temperature. Especially eyes, brain, stomach and flank muscles are heated. "Warm-blooded" sharks can move faster, process stimuli faster and digest faster than other sharks. The temperature in the flank muscles of a great white shark can rise to 27° Celsius at an ambient temperature of 8° Celsius.