The 7 Senses of the Sharks

In the depths of the oceans, hunters must have excellent senses to locate their distant or hidden prey. In over 400 million years of evolution, sharks' senses have evolved into high-performance sensors. They can see in the dark better than cats, they can perceive certain smells 10,000 times better than we humans, and they have a distinct sense of taste. They hear excellently, receive and feel even the smallest differences in pressure, feel currents and can even locate the electrical fields of their prey.

Photo © Shark Foundation

Photo © BPA

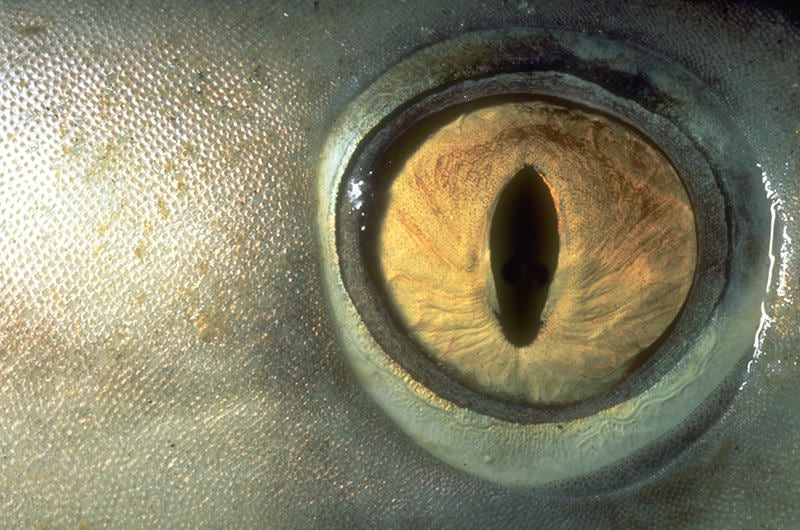

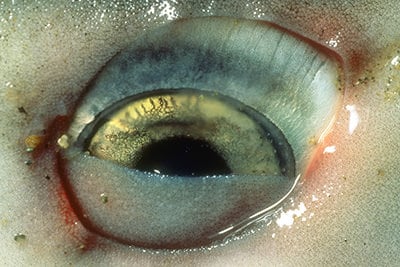

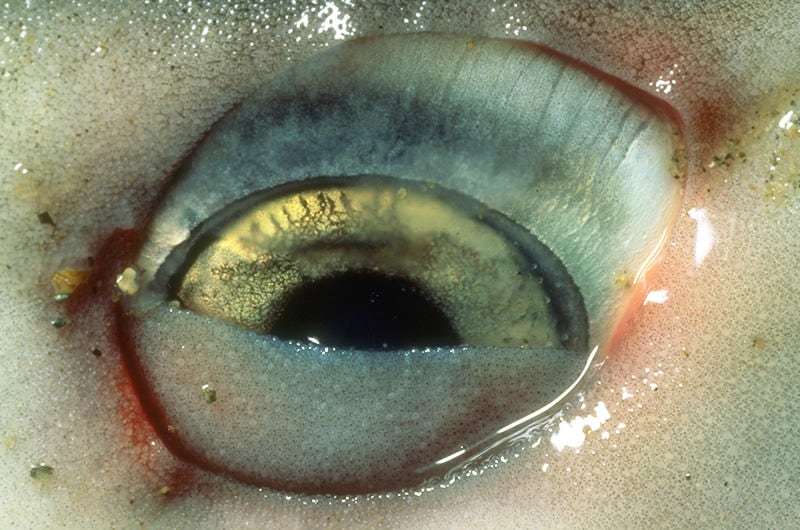

Sight

Objects can only be detected underwater in a range between 0 and – depending on water conditions – up to approx. 50 m. Whether hunter or prey, whoever sees better has an advantage. Sharks see well, and by means of a light amplifier or Tapetum lucidum in the twilight even better than cats. They also recognize colors and minimal contrast differences. The eyes are made of the same components as those of other vertebrates.

To protect the eyes while feeding, grey sharks have a third eyelid, the nictitating membrane, which they can slide over the eye. Other shark species, such as the great white sharks, turn their eyes backwards during feeding to protect them from injury.

Photo © BPA

Smell and Taste

Smell

The nose openings of the sharks are located below the muzzle. The nasal cavity, unlike in humans, has no connection to the throat. When swimming water flows through the nasal cavity which is lined with lamellae and are covered with olfactory receptors. Touch-sensitive barbels in front of the nose are found especially in bottom-dwelling sharks such as bullhead sharks or nurse sharks and which help them track down prey. The sharks' sense of smell is amazing. They smell certain substances such as the amino acid serine, a component of fish blood, 100 million times better than we humans.

Taste

The decision whether a prey is eaten or not ultimately depends on its taste. This is dangerous for humans, although very rarely. If a human attracts the attention of a shark, a shark may take a test bite to determine whether the human is edible. Many shark injuries are caused by such test bites. Usually the shark will let go of the human after the first bite, which unfortunately can be fatal. In many examined bite wounds no tissue is missing. The shark may bite but not bite off any tissue. Humans simply don't taste like fish.

Photo © Shark Foundation

Hearing

Sound travels underwater about four times faster than on land, with low frequencies disappearing less quickly than high frequencies. Hearing is thus an important sense for sharks. They react especially to low-frequency, pulsating vibrations in the range of 25 to about 600 Hertz, a frequency range that picks up vibrations of sick or wounded animals. Some shark species can thus locate their prey precisely over several hundred meters.

Although sharks do not have visible ears, their hearing is one of their most important senses for hunting. Especially their inner ear is excellently developed. Not only does it perceive sounds but as in humans is also responsible for balance and orientation.

The two hearing organs are embedded in the skull cartilage, directly behind and above the eyes. They are only connected to the outside world by an endolymphatic duct that ends in a tiny pore on top of the head.

Photo © BPA

Waterpressure sensors

Pressure waves

Pressure waves are perceived by sharks on the one hand by the lateral line organ, on the other hand by many pit organs distributed over the body.

Lateral line

The lateral line organ of the sharks is often strongly branched in the head region and then runs relatively straight to the tip of the tail. It contains sensory cells embedded in jelly and is connected to the surface by small pores. The jelly transmits pressure waves to the sensory cells. The lateral line system, as well as the hearing, is very sensitive in the range of the pressure waves emitted by injured fish.

Pit organ

The so-called pit organ consists of two enlarged overlapping placoid scales that cover a small pit in the skin. At the bottom of this pit is a collection of sensor cells. Pit organs are found in large numbers on the back, sides and lower jaw of some sharks. Their exact function has not yet been clarified, but sharks can perhaps register mechanical stimuli such as water currents with their pit organs.

Photo © BPA

Touch and feel

Shark skin contains highly sensitive pressure and temperature sensors. Some of these sensors are so sensitive that they can register skin movements of only 0.02 mm. The sharks use these sensors to feel touch, water currents and temperature changes.

Photo © Shark Foundation

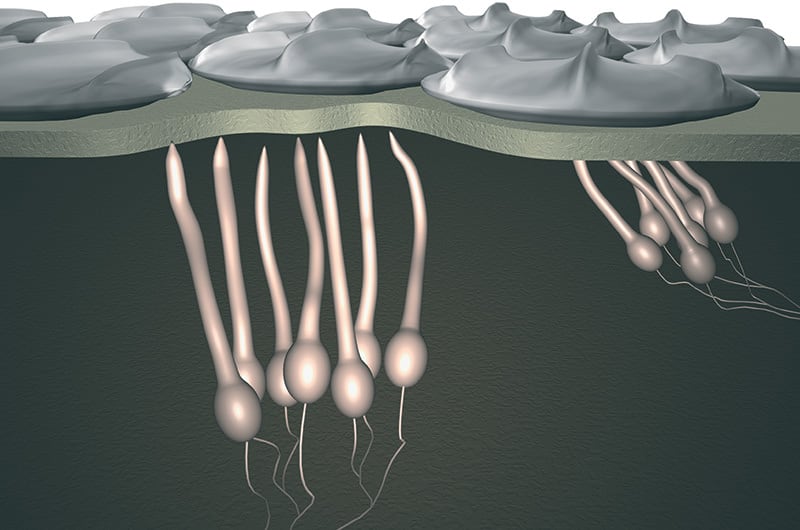

Electro-perception

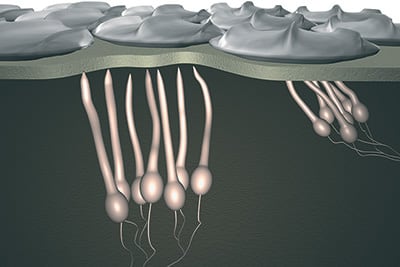

Probably the most fascinating sensory achievement of sharks is their perception of electrical fields. Every living creature produces electrical fields, be it with its heartbeat, muscle movement or brain. No matter how well a prey animal hides or camouflages itself, it cannot hide its electrical fields.

The electrical sensors of sharks are the Ampullae of Lorenzini. They only occur in sharks and rays and consist of the actual ampoules and a long tubule filled with a gelatinous substance that ends in a pore. Hundreds of such pore groups are visible on the head and especially in the snout area of sharks. Since the electrical impulses of prey animals are very weak, the electrical sensors only function in a range of a few tens of centimeters.