Many shark species, especially the pelagic forms, follow their prey or visit their mating and parturition sites. In doing so, they often come close to international fishing fleets and are killed deliberately or as bycatch. Many high-sea species are thus strongly threatened. To better protect these sharks, we need to know more about their migration routes and when they migrate.

Mako sharks are particularly endangered on their migrations.

Photo © Shutterstock

Background

Pelagic sharks are typically very mobile and migrate over long distances. On their regular migrations, or while tracking their prey they cross the territories of different countries and are therefore either protected or not protected by different legal systems. Since international fishing fleets usually target the same fish shoals as sharks, or target pelagic sharks because of their fins and meat, most high-sea sharks are highly endangered and their populations are declining at an alarming rate. In order to better assess the threats to these sharks from the international fishing industry and to be able to take effective, internationally coordinated and sustainable conservation measures, we need to know more about their migration routes, both spatially and temporally.

Another problem for the protection of high-sea sharks and their sustainable management is that estimates of their population sizes are usually based on the notoriously inaccurate data of shark catches. With accurate information on the temporal and spatial occurrence of sharks, the models used to calculate population sizes can be greatly improved.

Another problem for the protection of the high sea sharks and their sustainable management is that estimates of their population sizes are usually based on the notoriously inaccurate data of shark catches. With accurate information on the temporal and spatial occurrence of sharks, the models used to calculate population sizes can be greatly improved.

Makos are listed on the Red List of the IUCN as globally endangered. The reason is overfishing and overexploitation of the stocks. Smooth hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna zygaena) are globally threatened because of their fins, which fetch high prices on the Asian fish markets (Red List of the IUCN: "vulnerable") and there is a risk of extinction.

In addition to precise information on the migration routes of pelagic sharks, population-genetic analyses are equally important. With their help it can be determined, for example, whether and to what extent individual populations of a species mix. Are they isolated or is there a strong genetic exchange? In addition, with a sufficiently large number of samples, the population size can be estimated with relative statistical accuracy. The Shark Foundation also supports the laboratory of Prof. Mahmood Shivji in these analyses with the project population genomics of large shark species.

Goal

The aim of the project is to collect as many movement profiles of individual sharks as possible in order to be able to make statistically significant statements about their residence probabilities with respect to time and place as well as population size. This data can be correlated with the known positions of international fishing fleets. On the basis of this scientific data it should be possible to convince politicians and the management of international fisheries, e.g. ICCAT (International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas) or cynically "International Conspiracy to Catch All Tunas", to better protect these sharks.

The project is a summary of two other previous projects:

- Migrations of hammerhead sharks (2019 - 2021)

- Migrations of Mako sharks (2015 - 2019)

Methods

So-called SPOT (Smart Position and Temperature) satellite transmitters are used. These transmit their data as soon as the antenna is above the water surface, and PSAT (Pop-up Satellite Archival Tag/Pop-up Archive) transmitters, which detach themselves from the animal after a predetermined time, drift to the water surface and transmit their collected data material (archive). Both use the Argos Satellite System.

PSAT transmitters are usually attached to a spear and inserted below the dorsal fin of the shark. SPOT transmitters are more complicated to attach as care must be taken to ensure that the antenna is above the water surface as often as possible. For slow-swimming sharks like the whale sharks, they can be equipped with a float, similar to PSAT transmitters, with a long cable attached under the dorsal fin. For fast-swimming pelagic sharks, they are usually attached to the dorsal fin.

Results

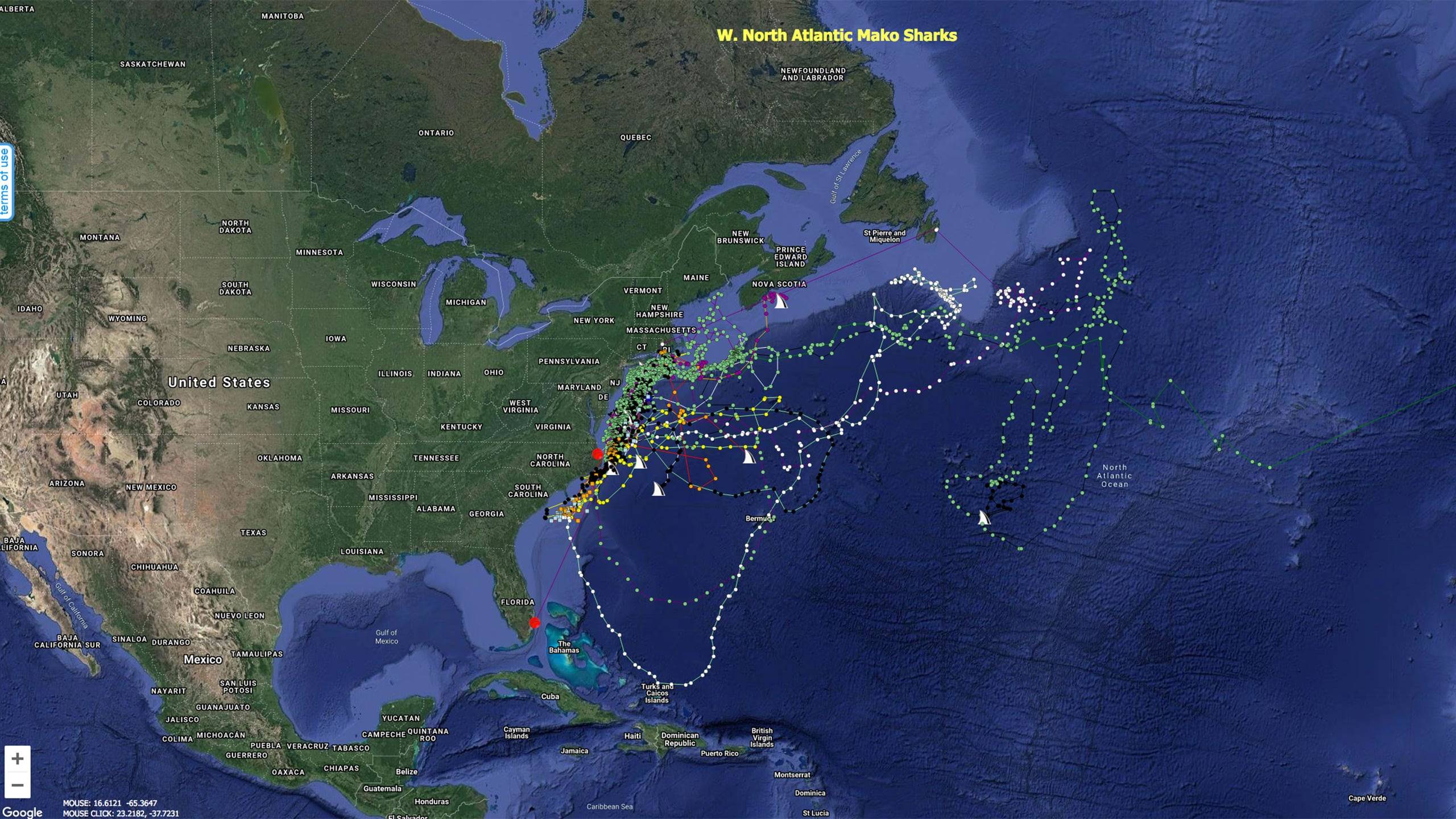

Makos

New Zealand: The Foundation has exceptionally financed two satellite transmitters for the study of mako sharks in the Indo-Pacific region. The two mako sharks with tags funded by the Foundation, Gabi and Heinrich, stayed mainly in the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of New Zealand where makos unfortunately are not protected. Interestingly, all 13 marked makos in this project stayed for months in the coastal region of New Zealand and then swam at high speed in a northerly direction, most of them into the regions Tonga and Fiji, one into the Coral Sea. Most of them returned to New Zealand afterwards. Gabi and Heinrich covered 13,700 km (Gabi/587 days) and 7,700 km (Heinrich/280 days), respectively, in the time period in which the transmitters provided data.

North Atlantic: In 2018, Mahmood Shivji's team was able to show with its migration and genetic analyses that the mortality rate in the Mako fishery was underestimated by a factor of 10, which directly led to emergency catch restrictions by the NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) in the western North Atlantic. The ICCAT has, as expected, hardly reacted at all.

Eastern North Pacific: The project is a collaboration between the NOAA and the Guy Harvey Research Institute (GHRI). Mahmood is director of the GHRI. The NOAA provided the team satellite data from 62 makos for analysis which is currently in progress.

Smooth hammerheads

Smooth hammerhead sharks migrate over longer distances, but almost nothing is known about their migration routes. Fishery management authorities and organizations urgently need accurate data on migration routes at the population level, preferred habitats and areas of overlap with the fishing zones of high-sea fishing fleets. This study, funded by the Shark Foundation, aims to provide information on the migration of this shark species and to support international fishery authorities in establishing protection zones and conservation periods for this shark species.

Based on the results of this project, seven scientific publications have been published so far.

Project Status

In general, the Foundation does not finance satellite transmitters for cost reasons. For example, the price of one transmitter can finance an entire short project. However, since the analysis of migrations is essential for shark protection, the Foundation supports the laboratory of M. Shivji in the nontrivial analysis of the Argus satellite data.

The Mako Project has already contributed substantially to the protection of this endangered shark species. The data also serves to lobby in Europe for better protection of makos. ICCAT and the European Fisheries Commission have not implemented any really useful measures for the protection of the makos, despite massive pressure from European shark protection organizations.

Administrative Details

Project Status: ongoing project since 2015.

Project Leader: Prof. Mahmood Shivji

Funding so far: CHF 48,700